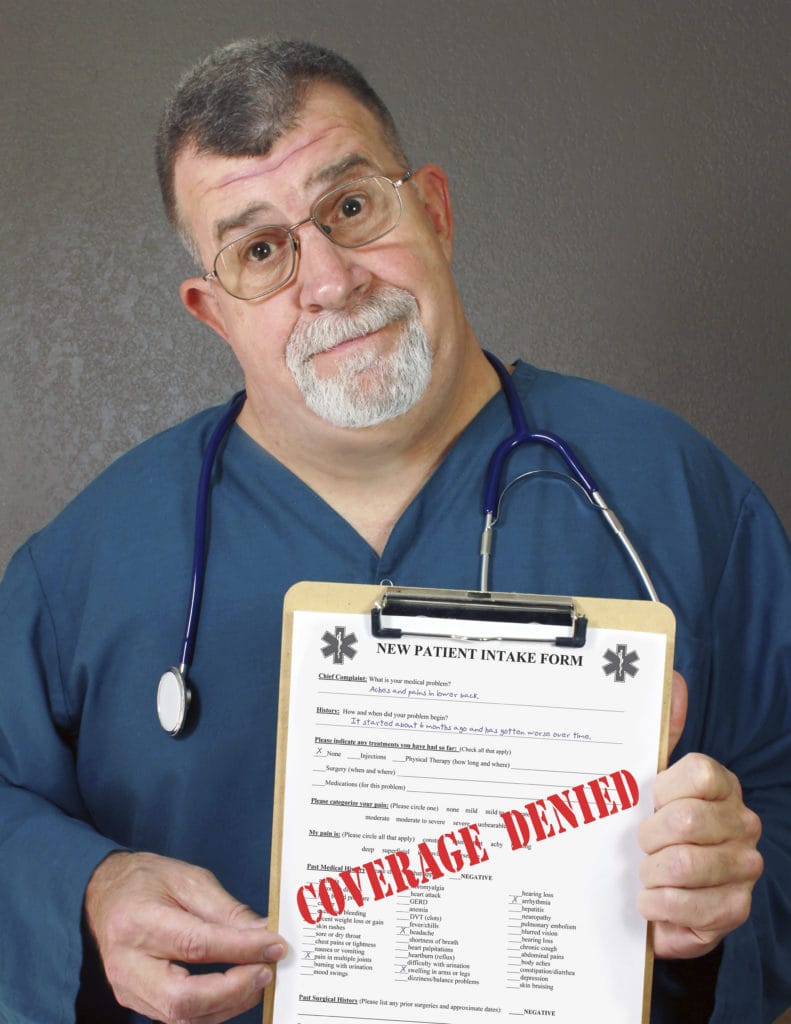

The family’s first-born son was away at college when he became a heroin addict. He was 21 and in the throes of detox at a long-term residential treatment center when his parents learned this sobering news: their medical insurance would not pay the $8,000 bill. “I used the savings bonds I inherited from my grandma to pay for it,” said the mother of the addict. That was in 2010 — or three heroin relapses ago and two overdoses, when her son was technically dead for a few minutes. Not even that qualified as a life-threatening condition, which is required by many insurance policies before they’ll cover live-in rehab. “He has to fail at a few more outpatient programs before they will consider covering it, and [my son] thinks it will take him six months of inpatient care to stay clean,“ added the parent, 52. “It takes that long to start your life over.” As heroin use soars in the U.S., addicts seeking to get off drugs are finding their insurance companies will often deny them all but outpatient treatment — until they relapse. Addiction experts say relapsing into substance abuse is expected, part of the disease and recovery. Dr. Jason Powers, chief medical officer for Right Step addiction treatment centers, said studies show that it takes an average of seven “quit tries” and an average of four treatment “episodes before total abstinence is reached.” Even then, treatment providers say, insurers typically will require the addict to have already tried outpatient care and failed to stay drug-free without 24-hour patient supervision, counseling and new coping skills. The decision is based on the fact that while miserable, the simultaneous vomiting and diarrhea, profuse sweating, runny nose and eyes, fever chills and other heroin withdrawal symptoms are not life-threatening. Heroin addicts might disagree.

Spike in Deaths

In the last several weeks, there have been at least 22 overdose deaths in Pennsylvania linked to a strain of heroin that authorities estimated to be 10 to 100 times stronger than morphine. It’s been laced with fentanyl, a powerful opiate, and it’s been mostly young people dying. For easily six months now, there’s been a spike in heroin addiction admissions at The Recovery Place, a drug and alcohol treatment center in Florida owned by Promises Behavioral Health. There, 70% of clients are fighting opiate addictions, half of those for heroin, said Peggy Robinson, director of utilization review. Nationally, the picture is grim. There have been crackdowns on “pill mills” that dispense pain medications without prescriptions and for cash. But use of prescription opiates has reached epidemic levels: 15,000 deaths yearly in the U.S. are now linked to prescription pain pills. Treatment centers report that addicts start with opiate pain pills such as OxyContin, Roxycodone, Percocet, Vicodin, Dilaudid, Lortab and morphine. But they cost about $30 a piece, and addicts quickly progress to inhaling chopped up pills before someone tips them off to IV heroin, which costs $10 or less per bag with a high that lasts longer than pills, The Recovery Place reports. A typical heroin user can easily reach a $100-a-day addiction. But users are not aware that dealers are stretching their product and take by cutting the heroin with fentanyl, a form of morphine. Against that backdrop, Robinson said she has a team that seeks insurance coverage for residential heroin treatment. “It’s rare to see someone in residential treatment for an opiate addiction [including heroin] treatment” with insurance covering it, added Lori VanValkenburg, intake coordinator for The Recovery Place, which also offers outpatient care. “Technically, there is not necessarily a medical necessity for inpatient care for heroin [withdrawals]. Drugs like suboxone (a narcotic, like methadone given to help addicts ease off of opiates) could be done on an outpatient basis. “The thing with outpatient treatment,” VanValkenburg added, “is that nothing is changing: you’re going to get a prescription of suboxone for the withdrawal — I can’t tell you how many people are selling their suboxone and continuing to use heroin — then go back to your old way of life. With in-house, you leave everything behind.” RELATED: Mixing Drugs Can Prove Fatal Coverage can vary widely from state to state. The California Department of Insurance establishes minimums for insurance companies in the state, and deputy press secretary Patrick Storm said that a general Kaiser Permanente PPO policy is now the benchmark. “If it’s covered in that, it’s going to be covered in California … as the minimum standard for care,” Storm said. Other states may vary, and mental health providers nationally are still trying to understand how coverage may change under the new federal Affordable Care Act. The Kaiser policy spells out chemical dependency treatment coverage as providing for in-patient medical treatment for detoxification, which is generally a few days, in a Kaiser hospital at a rate of $400 a day. And under “chemical dependencies service exclusion,” it lists “services in a specialized facility for alcoholism, drug abuse or drug addiction.” It does provide extensive outpatient coverage. Whatever treatment, the math is daunting: Hydrocodone is the most frequently prescribed opiate in the United States with nearly 143 million prescriptions for hydrocodone-containing products dispensed in 2012, according to the Drug Enforcement Agency. As to insurance covering heroin addiction residency, in a typical case, a New York man in his 20s hooked on heroin was motivated to quit using and sought help at Unity Health System, where they told USA Today that the man’s insurance would not pay for his stay. Richard Caruso, head of the treatment programs, said the addict had insurance, but that it required him to first try less-costly outpatient treatment for nine months. The reasoning: the same medications such as methadone that replace the heroin fix can be dispensed on a daily basis. “That’s a typical response from an insurance company,” Caruso told USA Today. “There are a lot of people who need inpatient services, but, because of denials from insurance companies, are in outpatient.” Yet the gnawing cravings for heroin are among the most miserably intense, said a handyman addicted for decades to heroin. Handsome and tanned, the man in a gray T-shirt, work boots and jeans strolled into a low-slung methadone clinic in Long Beach recently about 10 minutes before closing. The large city with a large veterans hospital has dozens of methadone clinics. He was the last of the people — teens to middle-aged and a few elderly — who’d streamed in since 6 a.m. With the daily methadone dose, he can work full time as a commercial building maintenance man. Without it, said the 57-year-old, he’d be dead. The Long Beach junkie said he went straight from marijuana to heroin before high school graduation. It was not until age 43 that he got clean, partly due to not being ready to quit, eventually because shooting heroin up his veins was cheaper than the long-term rehab he could not afford. Methadone, like suboxone, is a replacement for heroin and other opiates that is itself addictive, but the man said after 14 years, he’d not be clean without it. Nobody gets clean without help, he added. And help costs money. Until Covered California provided him coverage via Medicare, he’d spent most of his earnings on the methadone, went without a car and rode the bus to work. “I’ve been using heroin 35 years, since I was 16, in high school. If you really want to get off heroin and you’re ready, you’re on your own. If you don’t have insurance or the insurance [is bad], you’re really alone with it. Your either going to continue using, or you decide to give up … and overdose. Maybe on purpose — you’ve got nothing else.”