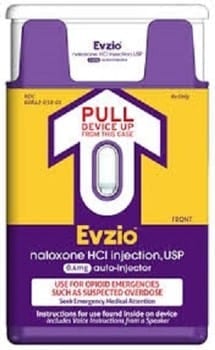

With stunning speed, on Thursday the FDA approved an injection device designed to deliver naloxone — a drug that can reverse an opioid overdose — for use in the home and other non-hospital settings. The approval comes after a four-month, fast-track priority review, and may represent a tipping point in how heroin and prescription opioid addiction is approached in this country. Called Evzio, the hand-held device delivers a single dose and provides verbal instructions. “This is a very big step in the de-stigmatization of addictions because it puts saving the life of the addict above other considerations,” says Dr. David Sack, CEO for Promises Behavioral Health. Although not a treatment for addiction, “It will allow users to live to fight another day.” Intense interest in naloxone has come in response to growing numbers of overdose deaths among heroin and other opioid drug users. Fatal drug overdose has increased six-fold in the last 30 years, and in 2012 alone, more than 16,000 died from opioid overdose. In the U.S., enough prescription painkillers were prescribed in 2010 to medicate every adult for a month. “We are in the middle of a prescription drug epidemic, and the rates of heroin use are escalating rapidly,” said Dr. Sack. “The rapid rise in opiate overdose deaths is directly related to the prescription drug epidemic. There is little doubt as to how we got here.” By all accounts, naloxone is a miracle in a vial. The nontoxic, non-addictive drug can reverse the effects of an opiate overdose within minutes of administration by stopping potentially fatal respiratory depression. In fact, based on a 2010 nationwide survey of 188 local prevention programs, the CDC reports that from 1996 to 2010, 10,171 lives were likely saved by timely injection or nasal administration of naloxone. Even prior to the FDA’s approval of Evzio, naloxone’s extraordinary effectiveness has had a growing number of health officials and community-based programs scrambling to get the drug into the hands of those who are most likely to be on site at the time of an overdose: police and first responders, but more to the point, families and friends of opioid abusers. But approval doesn’t mean that naloxone will suddenly be widely available, largely due to state laws. Although it’s legal to prescribe naloxone in every state, states generally discourage or prohibit the prescription of any drug to someone other than the intended recipient or to a person the physician has not examined. In order to address this, several states have removed legal barriers to those seeking emergency administration of naloxone and some have also passed “Good Samaritan” laws protecting those who summon emergency responders. Although FDA approval doesn’t affect state law, for those seeking to broaden access, it could help. “The FDA explicitly said that naloxone can appropriately be prescribed for someone other than an opioid user, writes Corey Davis, an attorney and deputy director for The Network for Public Health Law, in an email. “Although that’s a decision that’s made by the states, this explicit endorsement should spur state medical boards into permitting such ‘third party prescription’ which in most if not all states does not require legislative action.” But even as some states are rushing to pass legislation to broaden access and remove liability for prescribers and lay administrators, other states have been slower to react. Critics argue that naloxone opens a Pandora’s box of problems. They suggest that the benefits of the drug don’t outweigh the social cost incurred if reducing the consequences of a drug overdose leads to increased drug use. Maine Gov. Paul LePage argues that naloxone should not be available for home use “because it’s an escape and an excuse to stay addicted,” he said in a recent news conference. “Let’s deal with the treatment, and not say, ‘Go overdose, and oh, by the way, if you do overdose, I’ll be there to save you.’ ” But addiction specialists generally disagree. “There has been no evidence to show that more people will use drugs if there is an ‘antidote’ available,” says Dr. Michael Baron, director of Behavioral Health for The Ranch, an addiction treatment center in Nunnelly, Tenn. “The limited outcome studies that are available from the states that have legislated Good Samaritan 911 Laws show that having naloxone available in the home will save lives.” Dr. Baron, who is on Tennessee’s Board of Medical Examiners and chairman of the state’s controlled substance monitoring database oversight committee, has been working to reduce the opioid overprescribing problem in the state. “We are just now starting to see the results of less opioid prescriptions,” he said. But history shows that curtailing prescriptions can have unintended consequences. “As we have restricted access to opioids, some opioid-dependent people may be switching from prescription painkillers to heroin,” he said. “So another approach is needed, because the overdose problem isn’t going away. We need to augment legislation, regulation and education in order to enact the Good Samaritan 911 Laws in Tennessee and all 50 states.” Physicians and other clinicians who work with recovering addicts are among the strongest proponents of naloxone because addicts who have stopped using are at great risk if they relapse. During recovery, said Dr. Baron, tolerance to opioids quickly decreases. “In as little as three weeks, an abstinent addict can lose most if not all of their tolerance, he says. “The same amount of oxycodone used after treatment that was used before treatment will likely cause an overdose. Many times the first sign that a patient has relapsed is their death.”

Naloxone 101

Naloxone is not new. Trademarked as Narcan, Nalone and Narcanti, the overdose antidote has been around since the 1960s, when it was developed by a global pharmaceutical company. It was approved by the FDA in the 1970s, but it wasn’t until 1996 that community-based programs began providing naloxone to service providers, such as homeless shelters and treatment programs, as well as drug users, their families and friends. Naloxone is what’s known as an opioid antagonist. It works by blocking opioid receptors in the central nervous system, thus reversing the respiratory depression associated with opioid overdose. It can be administered intravenously, or by injection, or via a nasal mist. When administered intravenously, it goes to work in seconds. Several medications that target opioid receptors have been used successfully in the long-term treatment of drug addiction. One of those medications is naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, that’s been in use since 1984.